Interview: Building Cities Underground with Substeading

Transit experts Kyle Kirschling & Raymond Niles on homesteading beneath cities, abandoned tunnels, transit as real estate amenity, scaling prime locations, and the sordid history of trains in NYC.

You’re reading Startup Cities, a newsletter about startups that build neighborhoods and cities.

This week: an interview about building cities underground!

I have a few goals for these interviews:

To take innovators seriously, even if an idea sounds weird.

To ask the questions that an intelligent skeptic would have about an idea.

To go deep. How does the thing actually work?

Raymond C. Niles is a Senior Fellow and columnist at the American Institute for Economic Research and a former university professor.

Prior to embarking on his academic career, Niles worked for more than 15 years on Wall Street as senior equity research analyst at Goldman Sachs, Schroder's, and Citigroup, and as managing partner of a hedge fund investing in energy securities. Twitter

Kyle M. Kirschling runs an internal management consulting group at the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority focused on asset management and on improving infrastructure reliability for the subway division.

As an advisor to the New York City Transit Authority, Kyle sped up subway trains (reversing a 23-year trend) by conceiving a new operations strategy, saving two to four minutes per train trip and increasing on-time performance from 67% to 81% in 12 months, at zero cost. Twitter

Read their whitepaper on Substeading.

Themes

Meet Ray and Kyle

Substeading 101

How would Substeading work legally and politically?

Homesteading and its fairness

Auctions, Minecraft, and Radio Spectrum

Beneath Cities is a Wasteland and a New Frontier

The Tragic (and Unbelievably Corrupt) History of Underground Transit

Natural Monopolies, Rights of Way, and Privatizing the Subway

Digging Holes, Cost Disease, and an Insider’s Take on Why Tunnels Cost So Much

Flying Cars, Density, and the Knock-On Effects of Better Transit

Realistic Projects and Technologies Enabled by Substeading

How to Scale Prime Real Estate

Meet Ray and Kyle

Zach: Who are you and what are you building?

Ray: I'm Raymond Niles and I'm an economist. What I'm building is a more prosperous, free world. This project that I co-authored with Kyle on Substeading is one piece of that effort.

Kyle: I'm Kyle Kirschling and I'm building bigger, better cities! Since I was a little kid I’ve been interested in cities. I love the layers, the density, and that everything you see — except for the sky — is man-made. It's the epitome of civilization.

Substeading 101

What is Substeading?

Ray: Substeading is homesteading underground.

There's all this unused space underneath cities which is just a wasteland. We call it an underground desert. We want to legalize a process for people to put that space to productive use and to gain legal title to it.

We want people to have the benefits of legal title so that they’ll have incentive to use the space productively. Legal title and the profit motive allows them to finance the development.

The term “Substeading” was coined by Kyle. It comes from homesteading, which was what our government did to help America develop the unused, wide open Great Plains as quickly as possible.

The land we’re talking about beneath cities is also wide open. The question is: how do we make it productive?

In the case of homesteading, the government said: if you're a farmer and you agree to farm the land for say five years then we will give you title to that land. You'll get that 160 acres! This created a huge incentive, a land rush of people to go to the Great Plains and farm that whole area.

Today, America is one of the bread baskets of the world, a huge exporter of food. We feed ourselves and a lot of the rest of the world because this wasteland was privatized.

We want to do the same thing for the wasteland underneath the cities.

What sparked this idea of building stuff underground?

Ray: I have a strong interest in deregulation of the utility industry.

Kyle: I’m a bit of a train nerd, but I'm really a city nerd. There's just so many ways, we could move much further, much faster. The basic transportation system we have isn't that much different than 50-75 years ago. More people would benefit from living in cities if we could improve transit. It could make cities more attractive places, more affordable places, and more convenient places to get around.

What’s an example of a Substeading project?

Ray: It could be as simple as an electric utility conduit. But in this paper we focus on new transportation infrastructure.

How would Substeading work?

Let's say I want to put in a tunnel for my new private subway system.

What's the process look like to negotiate and to build in a world with Substeading laws?

Kyle: The first thing is to make sure that [the underground area] isn’t used by anyone. This is the “desert” part of it. There are some things underground. But the desert part is fair game. This prevents conflicting claims.

Then you would file some paperwork to say “I'm claiming this area.” With a certain period of time, five years or so, you must build something with productive value. When that's finished — when you've improved it — you would own it. The government would give you official title to that property and you’d own it forever.

Ray: We're advocating that governments enact Substead Acts at the state level, most likely. But it could also occur at the local or even federal level. They must enact enabling legislation for this to happen. Just like the Homestead Act, legislation would lay out what criteria you’d have to qualify your project.

In addition to avoiding conflicting claims, there’d be technical details like how close you can get to the foundation of other buildings. Obviously, you can't threaten or harm other people's property. And then you'd have to survey and lay out what you're proposing to do.

We want this to be as-of-right development. Light touch. Today it’s possible for private individuals to develop things underground, but it's ad hoc. It's a politicized process. You've got to pay off people, either legally or illegally. You might get subsidies. You might use eminent domain.

We're saying: none of that!

You have to pay for everything yourself. But you do it as-of-right. We take the politics out of it.

What’s the state of underground property rights in a typical American city?

Kyle: I don't think it's very clear. 15 years ago or so, someone proposed building a privately financed tunnel in New York underneath Long Island Sound. It wasn't clear who would even approve it!

If there’s someone out there in your audience who’s an oil and gas lawyer, we would be interested in hearing from them. It’s a very complicated area of law, which we’d like to learn more about.

Wasn’t Homesteading Unfair?

You model Substeading on the U.S. Homesteading Act. But one criticism of Homesteading in the United States is that it gave away valuable land. People got perpetual ownership. Then that land grew in value.

Much of that appreciation happened because the state or other people did positive things. Homesteaders captured value they didn’t really create.

David Colander and Roland Kupers, I believe, argued that it would have been better if we didn't homestead, but if we leased the land more on the model of Singapore or Hong Kong. They argue the U.S. government left trillions on the sidewalk by pursuing homesteading.

Isn’t there some truth to this?

Ray: In fact, the benefits of homesteading are precisely because the homesteaders got perpetual title. We don't want the government setting terms over the use of the land. We don’t want people to engage in a political process to develop the land. The best use is the one that maximizes profits.

This is one of the reasons why the United States is so much more productive than most of the rest of the world. To a greater degree than most of the rest of the world, we respect property rights and give the incentive to create value.

The argument that our farms are only productive because of what the government is doing is ridiculous. And I think we are as successful as we are because there's actual ownership of the property.

Kyle: I don't see the problem with them benefiting from the positive externalities of other people around them making improvements. Maybe the government did make some investments. That led to appreciation, but presumably people pay taxes for it.

One problem that occurs to me with leasing would be that you're asking [the entrepreneur] to pay for rights. We’re saying that no one is doing anything with this underground space! It's just sitting there. It's not of any value to anyone.

Whoever goes there first and makes it valuable shouldn't have to pay for that. They should own it. We're taking a moral stance that it should belong to the people who create value from it.

Auctions & The Minecraft Approach

Is there an analogy here with radio spectrum where we define 10 depth bands of underground land and auction them off to the highest bidder?

Does this make sense for Substeading?

Kyle: That would require you to design and choose routes for the auction. We also don’t want people to pay more than the fees necessary to cover the costs of government administration.

Auctions would probably be a step forward from what we have today. But we need the decision of routes to be up to the developer. It needs to make the most business sense, not the most sense for an auction.

Perhaps you could do it with big cubes that are a half a mile squared. Then you could buy the cube and use it as you want. But that would be a bit difficult I think…

The Minecraft approach to underground development!

*laughter*

Abandoned Tunnels, Fencing the Prairie, and Other Failure Modes

How do I prevent a developer from running a single copper wire all around underground Manhattan and saying, I've improved everywhere! Now I own all this property! Where’s the limit for “productive use”?

Ray: This is a legal matter. A lot of these principles have been established for surface property law. For example, you can’t buy a strip of land surrounding another person’s property and deny them access to their property.

Some of this would be developed through case law. Not everything has to be specified upfront in legislation. When disputes emerge, a judge weighs both sides and makes a judgement based on more fundamental principles of property rights.

So they would probably see the copper wire as a spurious claim. One benefit of Substeading would be the development of a whole body of common law for underground property just as exists for above ground property.

Kyle: But I think if you were using this cable that would be totally fine! But you would own the part right around it. Whatever you need to support the cable, which would be a small amount.

So your legislation gets passed, there's a gold rush and a hundred YCombinator-backed subway startups emerge —

Kyle: Yeah!

*laughter*

— I guess that’s the dream right?!

So they build a bunch of tunnels. But some fail and now there's a lot of unmaintained, abandoned tunnels underneath the city.

This is a hazard to public safety. Apartment buildings are going to fall through the earth at random times!

How do we deal with failed underground projects?

Kyle: Well, part of getting the rights may be a provision where, by filing the claim, you must be able to tell whether an unused tunnel would lead to collapse, depending on where it is in the soil. If that was a risk, you could require bonding.

But I think it would be better probably to resolve it in the courts. There’s existing approaches with mines to deal with that.

Ray: We could ask Substeaders to post a bond or get a guarantor: a company that specializes in this. If it were to be abandoned and if there are any structural issues, the guarantor would then shore up the tunnel.

If you require a guarantor then the guarantor bears the risk. The guarantor is like an insurance company, they'll charge a premium that reflects that risk. This means they have an incentive to vet whoever builds these tunnels.

Kyle: I think the profit motive helps a lot. I think [long-term abandonment] would be rare in practice because tunnels are valuable. If they go bankrupt, companies are gonna sell it and someone's gonna find a use for it.

We've had the experience in many cities that a tunnel gets built but they realize they don't have the technology to finish it. It gets boarded up for 10 years and they try again. Tunnels are so valuable that if they do go bankrupt, they would likely be sold.

Ray: These are expensive projects. The vetting will happen by Wall Street. It's gonna be hard to get financing for projects unless they’re providing a lot of value to a lot of people. I think this becomes a little bit of a science fiction scenario. We shouldn't let it stop the idea.

You say that where these projects meet the surface, say with a stairway, they must comply with existing rules like environmental review and zoning. But once they get underground, these things should no longer apply.

But what about soil health? What about some endangered mole rat or earthworm species whose habitat we’ll destroy by tunneling?

Won’t proponents of NEPA and other processes argue that the ecology below ground is just as important as that above ground?

Kyle: Don’t you think that most people who care about the environment would prefer that things be built underground? There's a guy running for City Council in Brooklyn and he wants to put everything underground!

I think this is an advantage of Substeading, which is much more difficult with surface or even with air rights. There really isn't much living down there. There’s not much that can survive. In a lot of places, underground is not even used for groundwater.

Substeading has far fewer environmental concerns. It leaves the human environment almost entirely untouched. A lot of environmental objections are actually about the built environment. We've got this road here and it's gonna add traffic. We've got these houses here and it’s gonna add shadows. If you compare Substeading to an equivalent project above ground it's a lot better environmentally.

Beneath Cities is a Wasteland (And a New Frontier)

You guys describe the ground beneath cities as a “wasteland.” I laughed at first because it felt harsh.

But if I had magic vision it would probably look like a giant empty space down there, except for pipes and a couple of subway tunnels in New York. And most things would be clustered right at the surface, right?

Of the space beneath an average American city, how much is used? Could you put a percentage on it? How much space is available for Substeading?

Kyle: Space is used but not very deep down. Everywhere you have buildings, it's used. In New York City, once you get below about 100-150 ft there's almost nothing, maybe a water tunnel here and there. But that's about 10 stories down.

Under the streets, things are clustered right at the surface: utilities and everything. Building foundations are close to the surface. In a city like New York where you have bedrock very little is built into it. Once you get to to the bedrock level it's pretty much free and clear.

Since property rights underground are not totally clear, we actually don't know what's there. I've been involved in construction projects and you often don't know until you start digging!

What about the ad coelum doctrine? This is the argument that people's property rights should extend from their parcel to the center of the earth, up into the air, like a giant pizza slice —

Ray: — I think it's called the Blackstonian wedge, from Blackstone the famous legal theorist. It's a ridiculous idea. It makes no sense. For example, if the Blackstoneian wedge was true, we never would have had air travel, right? You're passing through thousands of people's property.

Property can only extend into the space that you're using to create productive goods. That's why we have property: to create the goods that we need for living. Doing something on one's own property doesn't give you a perpetual claim either above or below it.

If we adhered to this idea we’d shut down progress. We wouldn’t have subway tunnels or air travel. Even radio waves pass through people's property. If that principle is enshrined in state law, we would want our Substeading Act to overturn that!

Kyle: Mineral rights are a good example. Air rights are often managed by the government, but mineral rights are often private.

Ray: Yep, mineral rights vary state by state. My mother grew up on the iron ore range in Northern Minnesota. Apparently if you buy property there, they've already rejected the Blackstonian wedge. You only own the surface. You do not own the mineral rights.

It's a separate deed. You have to buy the mineral rights separately. It can be owned by the mining company and they have the right to mine those minerals. In fact, they even have the right to move your house, so says the law in Minnesota.

The Blackstonian wedge is some law professor in his armchair not talking about the real world. It doesn't reflect reality.

Kyle: You do see it mentioned in real estate textbooks and dictionaries. But in practice it's not used.

Ray: This is why we need a Substeading Act! We need to clarify the ability of people to claim the commons underground. Right now there are no rules or it's unclear or there's Blackstonian wedges. We need to legalize the process.

The Tragic (and Unbelievably Corrupt) History of Underground Transit

Are there precedents for private companies going underground to build the stuff you’re talking about?

Kyle: Well even the railroads are a precedent to some extent. But even after general incorporation laws were passed and you could create a corporation, railroads were always treated differently. Part of the issue is that railroads had eminent domain. So they had special regulations so they could use eminent domain. You had to be a common carrier. You needed established prices. It was always kind of muddy.

There are some interesting examples though, like Alfred Ely Beach. He ended up buying Scientific American and making it into a real publication. But he had an idea for a Pneumatic Subway. He was not able to get permission because at the time streetcar companies [his competitors] were really opposed it. But he got permission to build a freight tunnel of a certain diameter.

It was just a demonstration tunnel, built to win public support. [Z: Beach’s visionary subway was crushed by corrupt NYC politician Boss Tweed on behalf of crony streetcar companies.]

Ray, do you know how it works with utility companies today? Do they own the conduits?

Ray: No, I don't think they own the conduit. The problem with utilities is that their profit level is set by the government. If they do something innovative and they make more money, they have to hand it back to ratepayers. So there's no incentive to be efficient or to innovate.

For example, let’s say they have some conduit. There’s a little space where you could run an internet cable and maybe increase bandwidth capacity or compete with the existing internet provider. There's no incentive for them to lease or sell this space. They have to hand extra profits back to ratepayers. They're basically run like a nonprofit.

Kyle: There was also the Rapid Transit Act of 1875. It created a bit more of a standard process for building a rapid transit line. That’s what led to the whole elevated network in New York. These are steam powered, coal fired trains running all over the city in a Jules Verne-like system.

The reason they didn't build underground was because of the legal uncertainty.

Ray: There was a lot of corruption. So Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed — he was being paid off by the surface line operators! They had to pay him off because that's the only way they could get the franchise to operate.

These were short term leaseholds. Surface operators weren't able to operate on a permanent basis. Boss Tweed preferred surface transit because they paid him.

Even though other cities like London and Paris got their underground systems decades before we did in New York, he kept saying no to the subways because he was in cahoots with the surface transport people.

In Chicago, the city council was called the Gray Wolves. They would only give five-year franchises to the streetcar operators or to these newfangled electric utilities which were operating.

Every five years your franchise would have to be renewed. Think about it! You're investing in infrastructure that has an economic life measured in decades, maybe 50 years! You have 50 year bonds to finance it! But every five years, the government could shut you down unless you hand them a big fat suitcase of money.

This is what happens when you can't develop as-of-right. Which is what we're talking about with Substeading. This is what happens when you don't have real ownership.

In a way, the rise of the general corporation is similar. The idea was to take politics out of chartering businesses. You no longer needed to get a special act of the legislature. Because, every time you do that, there's corruption. So they changed it to an as-of-right system where anyone can form a business to do anything as-of-right.

Kyle: Yep. In fact, the reason the first elevated lines got a toehold in New York City despite Boss Tweed was because he thought it was so ridiculous that it would never succeed!

Natural Monopolies, Rights of Way, and Privatizing the Subway

Can we trust private corporations with these services? Aren’t transit systems and electric grids natural monopolies?

Ray: I've never seen a natural monopoly. I'm a professional economist. I'm an economic historian. And I've never seen an example of a natural monopoly.

Businesses are often called monopolies when they develop a large market share. But they can only do that by lowering rates over time. Every company that gets a large market share is going down the demand curve.

The only way you can increase the number of people you sell to is by figuring out how to sell at lower and lower cost. That was true for every so-called monopoly, whether you think of Rockefeller's Standard Oil Trust or the early electric utilities.

The real monopolies, which I call coercive monopolies, are when the government bans competition. In the case of utilities, government controlled access to the rights of way. If you're running a utility grid, you have to be able to create a whole network of wires and you need rights of way to do that.

Unfortunately, the government owned the streets. So they got to set the terms to do it. They reached deals with the utilities and they made it illegal for anyone to run competing wires into the utility’s service territory. They said, “Let us control the rates, send us lots of bribes every year.” Electric rates aren't as low as they could be. But that's not a natural monopoly. That's an unnatural monopoly caused by the government.

Substeading would make utilities competitive for the first time since the early days of utilities. Physically, any utility can compete with another utility and they could get access by going underground.

Why not just privatize the existing subway system?

Kyle: If you wanted to privatize the existing subway system, you would have a problem because you wouldn't have new competitors. So you'd have to chop it up in a specific way. Some people have said we could give each line to a different company and then prevent them from merging. But that’s not ideal. You want transportation to be coordinated.

You need a threat of competition. You don't have to have subways parallel next to each other to have competition. You just need that threat of competition and there's capital sitting there ready and waiting.

There are historical examples of railroads in a few cases where they actually did physically build something around another company. But that's one thing that I really am excited about with Substeading: the openness of it would enable you to have a coordinated system of transportation but also keep the prices low.

Digging Holes, Cost Disease, and an Insider’s Take on Why Tunnels Cost So Much

I read in a piece by Eli Dourado that one of the barriers to geothermal energy is our ability to dig holes deep enough. Are there barriers to digging that we have to overcome before Substeading would be a useful, wildly profitable, interesting space?

Kyle: No!

We put four examples in the paper of things that would be profitable at today's tunneling cost — at New York City’s tunneling costs! — which are the most expensive in the world.

Some projects would pay today. I also think you would see way more interesting and exciting things as tunneling costs came down in the future. Initial products would be smaller and shorter. But as things improve people could come up with new ways to dig. There’s tremendous incentive to so.

What about the Baumol cost disease argument that construction seems to be stagnating or getting worse? Isn't this a barrier to Substeading?

Kyle: Well, I think that's why we need Substeading. It’s true that tunneling costs are expensive. I don't know if this is the case around the world.

In New York the major tunneling projects are all by the public sector. There may be a private contractor. There may be some competition for the jobs. But they're still basically the government deciding what the project is going to be and roughly what it's gonna look like.

Let me give my disclaimer that the thoughts and opinions I'm expressing do not necessarily represent those of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

But I've been in meetings. A lot of what I do is trying to speed up the subway. If you want some kind of a change made to the existing system, it's very difficult. But if you want a design guidelines change so that it's incorporated into a newly-built system then they'll do whatever you want.

We'll put stuff in the design guidelines that makes tunnels cost that much more per mile. As a result, we get that much less of it. We add crazy fire suppression systems and change the way the lights are designed. It’s a bit like NASA. The major projects are all being led by the public sector.

Flying Cars, Density, and The Knock-On Effects of Better Transit

You use the term “revolutionary improvement” in urban infrastructure in your paper. What innovations are possible with Substeading?

Kyle: What if you could get anywhere around the city where you live in half the time? What if you could travel twice as fast on average?

Just think about how that could change your life. You could go to a school that's a little better match with your interests. You could commute to a job that's a little bit better for you. With a dating app you can find a little bit better life partner!

And imagine extrapolating higher and higher speeds of transportation. With supersonic planes and other innovations the whole world would be like one city. You would have access to all the restaurants and all the best doctors and everything around the world.

One of my favorite books for the last couple of years is Where’s My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall. He argues that widespread use of aerial vehicles would push against dense cities. In his world, people move out to rural areas and suburbs.

It seems like Substeading pushes in the opposite direction. It's most useful and most relevant for dense cities. Can you talk about these pressures towards sprawl vs. density with Substeaded transit?

Kyle: There are opportunities in both directions. It depends on which technology advances the most.

Consider telecommuting. People are concerned about the public transit system and whether people are going to use it. But that’s comparing telecommuting to the transit system we have today. If you made it twice as fast and twice as comfortable and easy, then maybe telecommuting wouldn't look quite as attractive.

It also depends on the value of having things clustered. People may want to have more space to live. Or, if people are telecommuting to work, then they might actually want to be closer to people.

Ray: Substeading would increase the number of transportation projects. It's purely additive. For people who like cities, which I do and Kyle does, it makes New York denser and bigger. You can access areas further out. But that doesn’t harm people who want to get into their flying cars and live in some rural area. Let both technologies flourish!

Kyle: New York City is still growing in population. I think it would grow much more if the cost of housing were lower, if the transportation were better, if it was safer. There is tremendous value there if you could improve the transportation system. You can unlock a lot of value.

There still seems to be value to this clustering. I'm not sure how things will shake out with telecommuting. We don't quite know how office buildings will adapt. They’re expensive. It would be cheaper to just have office parks. But there seems to be value in having things closer together.

Realistic Projects and Technologies Enabled by Substeading

What’s your favorite Substeading project that would be profitable now?

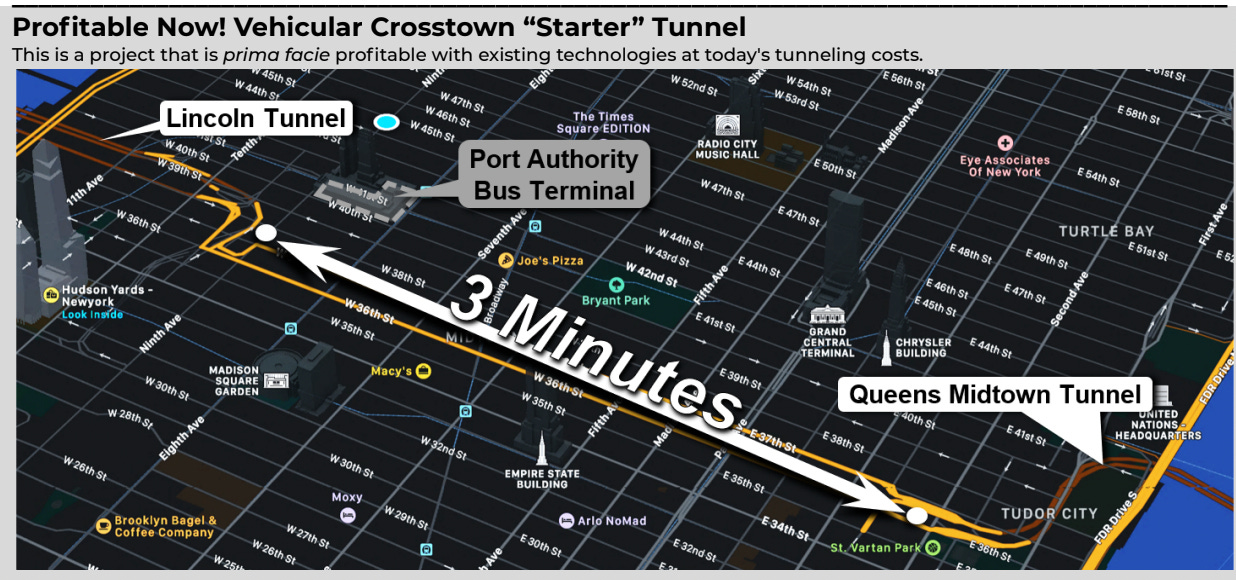

Ray: An underground tunnel connecting New Jersey with Long Island. It's ridiculous that if I go between Long Island and New Jersey, I've got to emerge with my car onto the surface of Manhattan. It makes no sense!

Anyone who really knows traffic in Manhattan on Broome Street heading to the Holland tunnel… well it's insane. It's smoke. It’s exhaust-belching cars.

I think it would pay for someone to build a tunnel underground. They could have exits in Manhattan, like an exit on the West Side and maybe one on the FDR and on 5th Avenue or something.

It would make people's lives a lot easier. And they would pay. We model a fare of $10 in the paper. But I'd pay 20 bucks!

When I was a kid, I traveled with my parents in Switzerland. We drove from Italy to Germany and there were some of the most amazing bridge tunnel combinations I've ever seen in my life. Miles and miles long. We paid like $50 total to use the tunnels. I remember my Dad saying every penny was worth it!

What are some realistic future technologies that you imagine deployed in a Substeaded world?

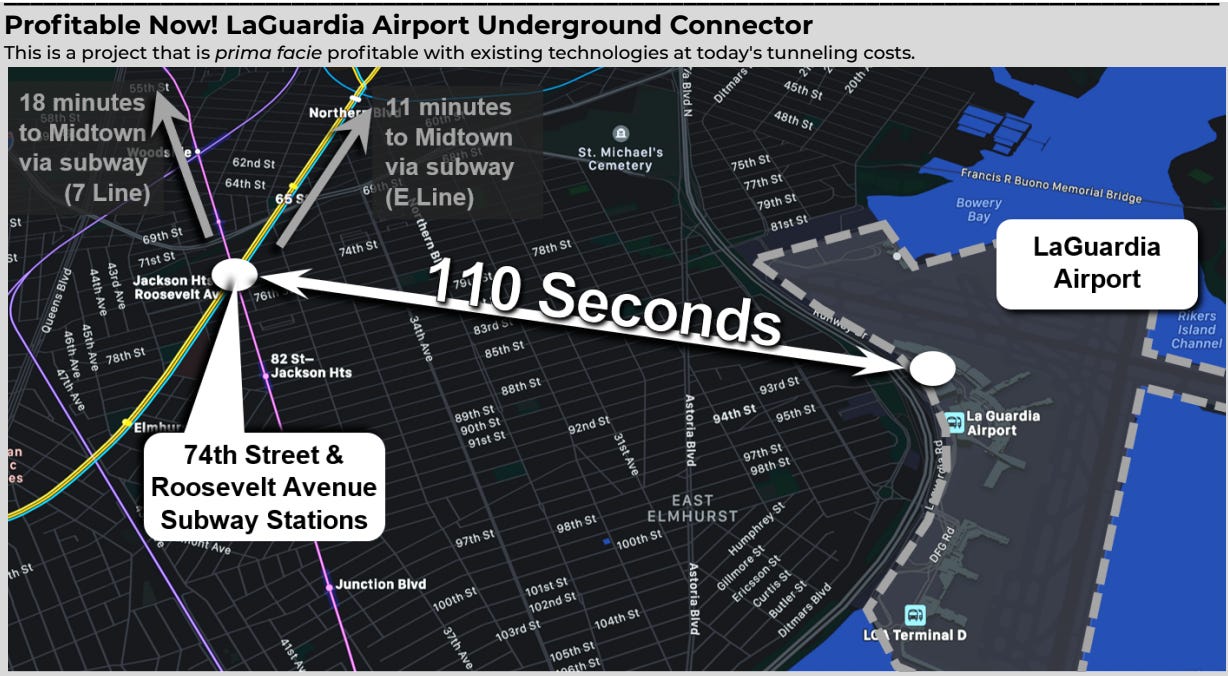

Kyle: My favorite is an underground high speed shuttle. Relatively short distance. Maybe a third of a mile, up to two miles. Something where you could connect two beautiful sights in a city.

One way to think of this is it would be like a portable lobby. It could be part of a nice development on the waterfront. But the development could be nearly as valuable as a property on top of Grand Central Terminal.

It can't be too short. If you could just walk there, you don't really need it. But if you could do it with a single tunnel then you can use conventional people mover technology: the kind of things at airports, just a bit more powerful.

So you'd be accelerating at the normal rate of a subway train. You continue to accelerate to 60 mph or so. Then you’re just slowing down. You could have a train every one or two minutes with a single tunnel at this high speed.

Projects like these might be a billion dollars or something. But it could be paid for by the increase in the rents. You'd be taking a property that's not worth much and giving it value as if it were on top of Grand Central Terminal.

How to Scale Prime Real Estate

It sounds like you're offering a way to scale a good location. I'm not actually next to Grand Central Station. But I’m sort of next to it because I can get in this magic underground people mover.

Kyle: Exactly. There is a bit of a time cost. In my ideal world it would be quick, like a minute or so. You wouldn't even sit down. Remember that the first elevators had seats on them. They were like a little vertical railroad. But if you could make it fast then people wouldn't even need to sit down. It could be seamless.

Ray: The largest undeveloped piece of land in Manhattan right now is south of the United Nations. So it's right on First Avenue. You can see it on the FDR. It's this huge open field. Imagine the difference in rent if that were moved (in terms of time) via an underground tunnel so that it was adjacent to Grand Central. You could charge much higher rents and that would pay for the tunnel.

Kyle: Yeah, that's a sweet spot. There’s also an opportunity right next to Grand Central. Not across the street. Literally right next to it. A Hyatt hotel is planned to be redeveloped. With Substeading you wouldn't even have to go across the street to get to Grand Central. Developers know transit is valuable. They advertise it today.

One of the themes in this newsletter is how real estate developers can eat more pieces of the urban environment. Instead of just owning the apartment building they own the apartment building and the park next door. Or the building, park, and the road out front.

Substeading feels like it adds new dimensions to how real estate developers can compete. It’s no longer: I have a pool in my apartment building. It's: I have a people mover and amazing broadband internet and I have a pool in my apartment building.

Could Substeading supercharge surface real estate developers?

Ray: Yes.

Kyle: Absolutely. That United Nations plot is a lot more valuable if it’s connected to Grand Central. There’s also more than transit. If you want a big floor plate for a trading floor or sports complex you could build at an unlimited size underground. Just connect it to your building using Substeading.

For example, Vornado Realty owns a bunch of buildings around Penn Station. They could internalize the costs of underground development and build their own pedestrian connection.

If you have smaller projects then the technology would develop and costs would fall. In 10 or 20 years more projects would be profitable just based on fares or other income streams. Then you could start building the next generation subway system.

I have to ask, have you sent this to Elon Musk yet?

Ray: I think that's sort of in the works…

Kyle: It's a new world for me. I don't really know the etiquette, so I'm not going to talk about it. But yeah, that's definitely something we're trying to do.

Ray: We did mail him a copy. But we know that's probably not the best way to reach him.

Kyle: If someone who reads this knows him or has thoughts about how to get to him, let me know.

Ray: We might be able send it to the Twitter headquarters now!

*laughter*

Zach: I guess we'll see, won't we? Thanks so much, Ray and Kyle!

Thanks for reading and don’t forget: Startups Should Build Cities!

Fabulous job interviewing and editing our comments! Thank you, Zach! And kudos for the launch of Startup Cities!