The Outsider CEO of Hong Kong

How John Cowperthwaite, a mild-mannered classics major, became the greatest city manager in history

You’re reading Startup Cities, a newsletter about startups that build neighborhoods and cities.

This week, a look at one of history’s greatest CEOs. This is a deep dive and you may need to click the title to see the full article, which is too long to read in many email clients.

—

I bet you’ve never heard of John Cowperthwaite (KOO-perth-wait)

He’s the CEO behind one of the most incredible growth stories of all time. He led his firm through incredible hardship, served millions of customers, and created billions in value.

But Cowperthwaite was no charismatic visionary. He was a quiet spreadsheet jockey with plastic glasses and a lawn bowling hobby. History barely remembers this humble Scotsman. Business history remembers him not at all.

Perhaps because Cowperthwaite never ran a company — he ran the city of Hong Kong.

The Outsider CEOs

In The Outsiders, William Thorndike profiles leaders like Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway, Henry Singleton of Teledyne, and John Malone of TCI. Thorndike noticed a pattern among this exceptional set. Each built enormously successful companies and beat the market for decades. But they were the opposite of the stereotypical television-interview CEO.

Outsider CEOs don’t have grand plans, but are flexible and opportunistic. They resist trends and fads. They aren’t flashy, but frugal. They’re often outsiders in the social sense, too: Buffett hails from Omaha, Nebraska, Malone from Milford, Connecticut, and Singleton from Hazlet, Texas. None studied “business” directly. But their businesses speak for themselves.

To understand why John Cowperthwaite belongs in the ranks of history’s great Outsider CEOs, we must first understand his legacy.

Hong Kong Before Cowperthwaite

Hong Kong began the 20th century as a backwater of the British empire, a rocky cove dotted with fishing villages. Times were not kind to little Hong Kong. Strikes paralyzed its nascent industries. Japan invaded in 1941 and marauding soldiers seized factories, debased the currency, and executed at least 10,000 Hong Kongers.

Once the Japanese left, the Chinese Civil War raged just beyond the city’s border. Then the Korean war sparked and export controls by the U.S. and U.N. crushed Hong Kong’s ports. By 1951, a journalist described Hong Kong as a “dying city.”1

Once the wars ended, the chaos of China’s Cultural Revolution began. Militants crossed the border and killed Hong Kong’s policemen. Communist agitators planted bombs on street corners.

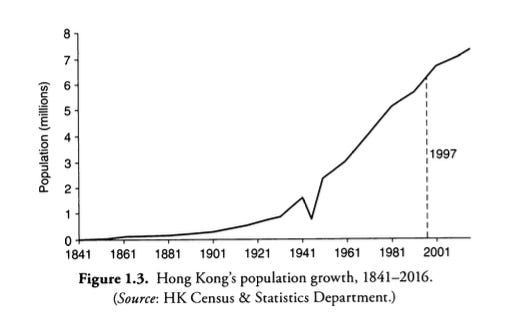

Hong Kong became a magnet for China’s desperate, persecuted, and poor. From 1945-1951, waves of refugees tripled the city’s population. In the six years before John Cowperthwaite took the helm, Hong Kong grew by nearly 1 million people.

Into the Maelstrom

Into this giant dumpster fire stepped John Cowperthwaite, a freshly-minted bureaucrat who studied the field of classics (which, let’s be honest, doesn’t sound like the ideal preparation to run a city).

Cowperthwaite began his rise as Director of Supplies, Trade & Industry, an unsexy job importing commodities like rice. His talents were clear. His first four years netted 67 million HKD in profits for the government department.

Tellingly, a young Cowperthwaite exploited the same trick that Warren Buffett later made famous: float. Traders deposited money when they ordered commodities. But the Treasury only paid post-invoice. So Cowperthwaite could hold this “float” in temporary accounts and use it to finance Hong Kong’s recovery from war. Clever.

Cowperthwaite then moved to the office of Financial Secretary, becoming chief of all economic matters in 1961. Here we see the young technocrat become Outsider CEO.

“The Greatest Dowry Since Cleopatra”

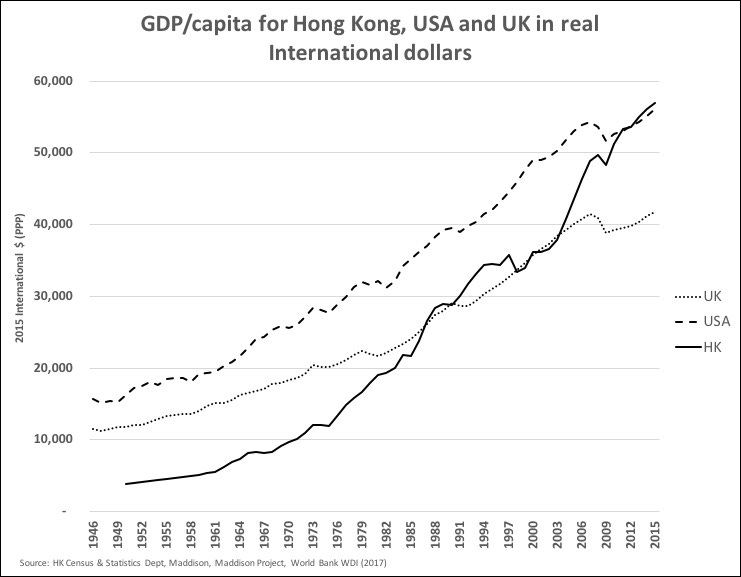

Great CEOs are measured by the long-term success of their firm. In financial terms, Cowperthwaite’s legacy is astounding.

When he assumed control in 1961, Cowperthwaite inherited a modest 500 million HKD cash reserve. His management of this reserve delivered incredible growth to Hong Kong and to the city’s bottom line. Ten years later, Hong Kong had 2.4 billion HKD in reserve, while also becoming a much more populous and prosperous city.

But Cowperthwaite’s practices really shine in their legacy. By the time China took control of Hong Kong in 1997, the city’s reserves had compounded to 330 billion HKD. One governor called it “the greatest dowry since Cleopatra.”

Yet by 2017, Hong Kong's “dowry” had grown even more: to 860 billion HKD. (If averaged from 1961, this is growth of over 14% per year.) Hong Kong is a city of about 7 million, so Cowperthwaite’s Hong Kong endowed each resident with 123,000 HKD, 45 years later. How’s that for saving for the grandkids?

Today’s Hong Kong operates unlike almost any other city. In 2011, the city paid a dividend. The Scheme $6,000 paid 6,000 HKD to every permanent resident in a bid to “leave wealth with the people.” Crucially, the city funded this dividend with budget surpluses, not debt or money printing. They did it again in 2018 and 2020.

Beyond Ideology

But, I can hear critics say, finances aren’t everything! What about Cowperthwaite’s record beyond money?

The political left pillories Cowperthwaite as a “market fundamentalist” villain, while the right imagines Cowperthwaite as a “small government” ideologue. Like most partisan takes, both are wrong.

Cowperthwaite’s surpluses weren’t the bitter fruit of austerity. Hong Kong has great infrastructure (better than any American city), modern buildings, beautiful parks, sparkling trains, and a world-class airport. By building densely, Hong Kong remains green, with nature just a subway or gondola ride away.

Cowperthwaite was also no hard-hearted nationalist. He found practical ways to accept the enormous flow of refugees to Hong Kong. Despite huge population growth, Cowperthwaite’s tenure saw real wages in Hong Kong grow by 50% and people in acute poverty fall from 50% to 15%. He removed taxes that were paid by the poor — such as on “nightsoil” collection.2 By 2015, Hong Kong had the world’s longest life expectancy, at 84 years. This is hardly the rob-the-worker “neoliberalism” of his critics.

Hardcore conservatives also miss the mark. As Hong Kong grew, Cowperthwaite spent more on education, health, and welfare. Seeing the city as a sort of mega-landlord, Cowperthwaite built low-cost housing to absorb refugees. (Although, ever the economist, Cowperthwaite’s subsidized housing included a modest return on the government’s investment and an interest charge.3) To this day, the city government owns nearly 100% of Hong Kong’s land — hardly a right-wing fantasy. Cowperthwaite also managed public utilities like buses, ferries, telephones, and gas as franchise monopolies with limitations on their profit.4

Cowperthwaite’s legacy transcends partisan politics. He amassed no great fortune for himself,5 but left an enormous endowment to the people of Hong Kong: not just a giant pile of cash, but a legacy of competent management that still pays (literal) dividends.

Let’s see how Cowperthwaite’s management style fits the Outsider mould.

Resist Trends. No Grand Visions.

Cowperthwaite led Hong Kong through an era with some of history’s most toxic development ideas. But, like all good Outsiders, he resisted them all.

To the popular idea that Hong Kong needed to protect its infant industries he said, “an infant industry, if coddled, tends to remain an infant industry and never grows up or expands.”6

When pressed to form a “Fair Rents Tribunal” to control rent prices Cowperthwaite retorted:

Let me say straight away that any attempt to bring rents generally under control would almost certainly make the housing situation worse, not better. The private builder will not build if his investment in housing, unlike other investments, is subjected to statutory restrictions.

When encouraged by the rising tide of Keynesianism to spend into deficit, Cowperthwaite argued against the burden on future generations: “previous generations have handed down to us a substantial public heritage by way of roads, ports, etc. almost completely free of debt,” he said. This should limit how much we burden “the next generation.”

Economists also pressured Cowperthwaite to form a central bank for Hong Kong. He didn’t. Against the advice of those around him, he let failing banks fail: “an economy with virtually no liquidations or bankruptcies is not really in a healthy state.”7 He also made it easy to start banks — only a single $5,000 license was required — so incumbents always felt the threat of competition.8

Cowperthwaite went to extreme lengths to maintain an independent strategy for Hong Kong. When British delegations wished to visit and hold regular meetings — no doubt to pressure Cowperthwaite into the latest flavor-of-the-month economic scheme — he invented “communications problems” that prevented him from having regular meetings (with deepest apologies, of course).

Cowperthwaite also refused to collect economic statistics. A city is not a simple machine, he reasoned. It’s dangerous to optimize for any single variable. If he collected statistics on Hong Kong, he knew others in the city’s management would use them to justify micromanagement of the city and “visionary” new proposals. So he starved the “visionaries” of data.

Radical Empiricism

But that doesn’t mean Cowperthwaite was an armchair theoretician. As with other Outsider CEOs, he was ruthlessly empirical.

Trend-following advisors told Cowperthwaite to form a special industrial bank to finance factories. But activists weren’t ready for the most obvious of challenges: Cowperthwaite asked them to find a single factory that wanted to open but failed to get financing.

They couldn’t. That ended the debate. Instead, Cowperthwaite advertised land on favorable terms to any factory that could find their own financing.

The Soviet strategy of 5-year plans, another 1960s trend, also came to Hong Kong. Cowperthwaite was not impressed. His assistant reported on Cowperthwaite’s belief that:

[A] plan is worth no more than the result it achieves. To achieve any result at all it must be based on assumptions that are least relatively stable and relatively sure.”9

But the evolution of Hong Kong had never been “stable and relatively sure.”

Cowperthwaite preferred the opportunistic experiment to the grand vision or the 5-year plan. In 1963, he slashed import duties on tobacco on the theory that a lower duty might yield higher revenue.10 It did. He hunted for creative, pragmatic revenue sources such as funding social welfare provisions from a government-managed lottery.

“Our Hearts Bleed for the Car Owner”

Let’s look at how Cowperthwaite applied radical empiricism to the eternal problem of cars.

Car ownership rose as Hong Kong grew rich. Car owners began to demand parking garages and surface lots on vacant government land. (We certainly know who won this battle in the United States.) But Cowperthwaite went against the car-centric 60s.

Cowperthwaite did not trust the airy projections of activists and their consultants. “As he engaged with an issue, he took considerable time to understand it in detail,” writes his biographer, “How did costs behave? What determined revenue? What levels of capital and labor were needed? ... The resultant deep understanding made him a formidable advocate, and adversary.”11

After careful study, Cowperthwaite pointed out that the cost of a single car parking space was enough to build a low-cost apartment to house 5 adults. Was one parking spot a better use of Hong Kong’s scarce land than a house for 5? No. (Here we see another cornerstone of the Outsider CEO approach: careful capital allocation strategiy and attention to opportunity cost. In this case, the “capital” is land.)

Publicly-run parking lots were “tacit subsidies for car owners,” Cowperthwaite argued, and owners should bear the full cost of their choices. His mega-nerd level of understanding gave him confidence to pull no punches with opponents:

My honorable friend [a prominent advocate for subsidies to parking] has given us another brilliant exhibition of special, indeed specious, pleading on behalf of his favourite cause, the provision of subsidized car-parks at the expense of the whole community.

He has once again made our hearts bleed for the wretched lot of that small, indigent and oppressed minority, the car owner, who, unlike the more fortunate 95% majority of our fellow citizens, is apparently denied the facilities of the public transport services.”12

Pragmatism & Megaprojects

Cowperthwaite was just as empirical and hard-nosed about big infrastructure projects. Past experience taught him that advocates and their consultants tended to understate costs and overstate benefits for their grand schemes.

He especially disliked the assumption that loss-generating infrastructure was “obviously” valuable because of supposed positive externalities or other social benefits. (We now have large data sets on megaprojects to show that Cowperthwaite’s intuition was mostly right.)

Pressure groups formed to demand the city build a tunnel between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon: the Cross-Harbour Tunnel. Cowperthwaite resisted. He understood that roads, bridges, and tunnels changed the economics of mobility, just as subsidized parking changes the economics of car ownership. The tunnel mostly benefited its users (car commuters), so why should Hong Kong spend so lavishly on a single interest group?

But Cowperthwaite was no thoughtless NIMBY.

Cowperthwaite didn’t block the tunnel. He had a private company build it, operate it, and charge tolls (an early use of the Build-Operate-Transfer model). Here we see another critical attribute of the Outsider CEO: frugality and negotiating skill. Cowperthwaite took a minority stake in the project and locked in 12.5% of tunnel revenues for the city.

It worked. Modern Americans are used to endless, dysfunctional infrastructure projects. So it’s hard to believe that construction of the Cross Harbour Tunnel finished a year early and the builder recouped all their construction costs after only three and a half years of operation. Cowperthwaite understood incentives and the power of skin in the game.

Thirty years later, the tunnel became property of the city (the “transfer” step of build-operate-transfer). It now generates significant revenue for Hong Kong.13 A pretty good deal, by an Outsider CEO.

Master of Capital Allocation

Above all, Outsider CEOs allocate capital well.

It may seem strange to view a city manager as “allocating capital” in the way that a private firm like (fellow Outsider CEO Warren Buffett’s) Berkshire Hathaway might buy stocks or bonds or acquire a business. Some will even find it distasteful to think of cities as economic enterprises constrained by the bourgeois logic of capital allocation.

American cities in particular seem resistant to the mere thought of cost and benefit. But there is no escape. Cities have finite resources. They must pick the goods and services they provide. Every product line, service, or land use has a cost structure and doing one thing precludes another.

As I’ve written elsewhere, cities are essentially owner/operators of a shared environment and provide the products and platform that define the value of that environment. Whether or not the city generates net revenue (or any revenue) from their choices — and whether or not leadership believe that costs and benefits matter — it is inescapable that cities allocate capital on behalf of their residents.

The core of Cowperthwaite’s capital allocation strategy is delightfully counterintuitive. While we think of a good capitalist as picking winners and losers in the market, Cowperthwaite mostly allocated capital via the entrepreneurs of Hong Kong.

Cowperthwaite made it easy to build a business and a life in the city. As the primary landowner and tax authority, the city of Hong Kong was like a modest equity investor in every business.

If Hong Kong thrived, land rents and tax revenues would rise. If Hong Kong stagnated, they would would fall. Since Hong Kong had a hard budget constraint — there was no national or state government to bail them out — there was a real feedback loop between good management and financial health. Cowperthwaite’s job was to make sure Hong Kongers thrived while providing the core mobility, security, and other services of a city in an economical way.

Cowperthwaite was explicit about his strategy to grow the coffers of Hong Kong:

I am confident, however old-fashioned this may sound, that funds left in the hands of the public will come into the Exchequer with interest at the time in the future when we need them.14

The genius of Cowperthwaite’s strategy is that he positioned Hong Kong to enjoy upside in the city without having to know which industries would work. For example, in the 1960s plastic flowers made up 5% of all of Hong Kong’s exports. But by 1970, wig manufacturing had eclipsed this export darling by growing from zero to 8% of all exports.15

(Other Outsider CEOs are famous for their wildly disparate investments. For example, though Henry Singleton’s Teledyne was known for high-end military technology, he also owned Water Pik — the teeth cleaning machine!)

What city investment committee or industrial strategist would have chosen “plastic flowers” and “human hair wigs” as the favored export industries of Hong Kong? Luckily for the city of Hong Kong, Cowperthwaite didn’t have to.

Focus on Cash and Extreme Frugality

The last pillar of Cowperthwaite as Outsider CEOs is his meticulous attention to cash flow.

Cowperthwaite’s budget meetings were fraught with worries about recurrent revenues and expenditures. A city might dial capital spending up or down as revenues grew or fell, he believed. But recurring costs, once assumed, are hard to change. “The growth of spending is a much more certain thing than the growth of revenue.”16

Cowperthwaite’s focus on cash led his approach to city services. While keeping prices low enough to avoid hardship for Hong Kongers, Cowperthwaite tried to cover the costs of basic services like water with fees or related revenue streams.17 As with the Cross-Harbour Tunnel, this kept tight feedback loops and avoided dysfunctional subsidies across services.

Cowperthwaite also planned for disaster. Warren Buffett famously keeps a massive pile of cash on hand to weather storms and to pounce when opportunity appears. So, too, did Cowperthwaite. He demanded Hong Kong maintain a full year’s revenue in cash reserves. Cowperthwaite understood tail risk — that it takes only one terrible external event to ruin a city that runs on the edge of financial stability. (“He saw a surplus or deficit as an output, rather than as a potential policy tool,” writes his biographer)

Outsiders are not optimists, but realists. While a stereotypical CEO might buoy his team with false optimism, Cowperthwaite forced his lieutenants to operate with extreme financial pessimism.

Never be optimistic about revenue, he counseled. Avoid deficits. Never plan to dip into reserves, even though sometimes we’ll need to. Revenue should limit expenditure except in the most dire circumstances. The great irony of Cowperthwaite’s paranoia is that his team’s financial pessimism led to year after year of surpluses and growth.

Cowperthwaite also lived this public commitment to frugality. Other Outsider CEOs are known for driving Toyota Camrys, running spartan offices out of strip malls, and refusing indulgences like a corporate jet.

Cowperthwaite refused to have his city-owned home redecorated at taxpayer’s expense and even refused air conditioning — no small sacrifice in the city’s steamy climate — since it wasn’t available to the average Hong Konger.

Janitor in Chief

“I tend to mistrust the judgment of anyone not involved in the actual process of risk taking.” - John Cowperthwaite

Why care about an obscure figure like Cowperthwaite?

In America, it seems our cities are always in the throes of some dreamy scheme. And, as an industry, American cities have atrocious financial performance. As regular readers of this newsletter have surely grown tired of hearing, I believe that our cities suffer not only from bad policies and decayed institutions, but from a lack of entrepreneurial management.

I do not mean “business-oriented” leadership or other euphemisms for crony capitalism or “tax breaks” or whatever policy-du-jour masquerades as real entrepreneurship. I mean literal entrepreneurs, with a long-term financial interest in a city, at the helm of management. This is a heterodox view, and a view that many people think is not just wrong but morally bad.

But Cowperthwaite’s Hong Kong shows the positive possibilities of entrepreneurial management. He acted like a CEO and had the latitude to take decisive action over a long period. The hard budget constraint of a free-standing city combined with intense adversity to give young Hong Kong startup discipline.

The result is not just financial success, but an overwhelmingly positive outcome for humanity by nearly every measure. And all this despite wars and chaos, absurd population growth, scarce land, and a total lack of natural resources. Surely our cities, which enjoy peace, beautiful locations with room to grow, and a level of prosperity unheard of in early Hong Kong can achieve much more.

Cowperthwaite acted with a rare humility when faced with complex reality (though this demanded a not-so-humble sense of conviction and focus). He rejected extravagant plans, was deaf to trends, and mercilessly prudent. By removing the common pitfalls of dreamy schemes, trend-following, and short-sighted finances from city leadership, Cowperthwaite delivered extraordinarily well on the basics of urban life.

In Alain Bertaud’s phrasing we might call Cowperthwaite history’s greatest “Janitor in Chief.” Not a visionary. But a competent and focused manager of finances, city services, and public spaces. In short, one of history’s greatest Outsider CEOs.

—

This article draws heavily on the excellent book The Architect of Prosperity by Neil Monnery and The Outsiders by William Thorndike. I recommend both.

Thanks for reading and don’t forget: startups should build cities!

Architect, 92

Architect, 165

Architect, 108

Architect, 203

As Financial Secretary he earned today's equivalent of about $115,000 USD per year — less than many junior software engineers.

Architect, 171

Architect, 209

Architect, 157

Architect, 172

Architect, 178

Architect, 186

Architect, 224

Architect, 202

Architect, 165

Architect, 143

Architect, 262

Architect, 109

>I mean literal entrepreneurs, with a long-term financial interest in a city, at the helm of management.

Did JC have such a financial interest?

Wasn't familiar with this story. There's a lot to learn from it. Thanks for telling it so well!